Having just finished the season finale of Lovecraft Country on HBO, I found myself underwhelmed by the last installment (and only the last installment). I should start by saying that Matt Ruff’s 2016 novel of the same name is one of my favorite books ever; certainly the best book I read in the decade in which it was published. And despite that high bar, almost without fail, Misha Green’s TV adaptation has been the novel’s superior in many ways—it takes the source material and adds additional nuance, thoughtfulness, and a gut-punch humanity to the book’s relatively dispassionate remove. I can only surmise that, in addition to Misha Green’s (and her cast and crew’s) incredible talent, some of the reason for this brilliance on top of brilliance is that the series was created, written, and directed by a a largely Black creative team and Matt Ruff, though extremely talented and insightful, is a White man.

But this last episode hasn’t sat well with me, and I have been looking both at why that might be, and also at why I might be wrong about it. Spoilers for both Green’s show and Ruff’s novel follow.

In so many ways, the television series starts where the book ends. And it’s not just the change in time period: Ruff’s epilogue is set six years after the main events of the novel, in 1955—the year that the entirety of the show takes place. And the final, grim, darkly funny beat at the end of the novel is taken as the entire premise of the show. The final story of Ruff’s mosaic novel, “The Mark of Cain,” more or less maps on to the season finale, “Full Circle.” Christina Braithwaite’s equivalent, Caleb Braithwhite, is cut off from the ability to work magic and, thwarted, he threatens the Freemans:

“It’s not over! There are other lodges all over America. They know about you, now. And they’ll be coming for you, but not like I did. They won’t think of you as family, or even as a person, and they won’t leave you alone until they get what they want from you. No matter where you go, you’ll never be safe. You—”

But he had to break off, for suddenly Atticus burst out laughing. […] They roared laughter.

[…] “What’s so funny?” But for a long while they were laughing too hard to answer.

“Oh Mr. Braithwhite,” Atticus said finally, wiping tears from his eyes. “What is it you’re trying to scare me with? You think I don’t know what country I live in? I know. We all do. We always have. You’re the one who doesn’t understand.”

Ruff’s thesis is that the cosmic horror penned by Lovecraft and his ilk holds no power over Black people because life under white supremacy is cosmic horror. All of America is Lovecraft Country if you’re Black. Green’s show doesn’t need to have an explicit moment of stating or spelling out that thesis. After all, the whole show has provided instance after instance proving that point: vicious, burrowing shoggoths are nothing compared to White sheriffs in sundown counties, the most grotesque and visceral interpretation of a kumiho loses its frightening power against the backdrop of the American occupation of Korea, and no monster or ghost or spell can ever compare to the sheer, heart-rending terror of the show’s unflinchingly accurate recreation of the 1921 Tulsa massacre.

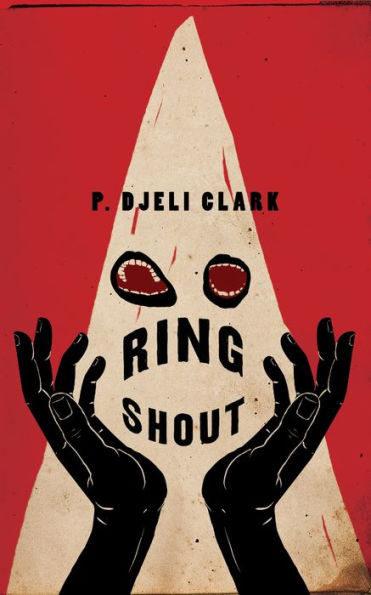

Buy the Book

Ring Shout

So the show knows, from the start, that the final knife-twist of its source material is the baseline from which it operates. And, given that freedom, it’s not afraid to go bigger and expand outward—thus, the show makes some bold, divergent choices. Green and co-writer Ihuoma Ofodire even wink at the audience about how much they’re steering away from Ruff’s book when, in the antepenultimate episode, Atticus mentions the differences between his lived experience and the in-world book, Lovecraft Country, written by his son, George: “Some of the details are different: Christina’s a man, Uncle George survives Ardham, and Dee’s a boy named Horace.”

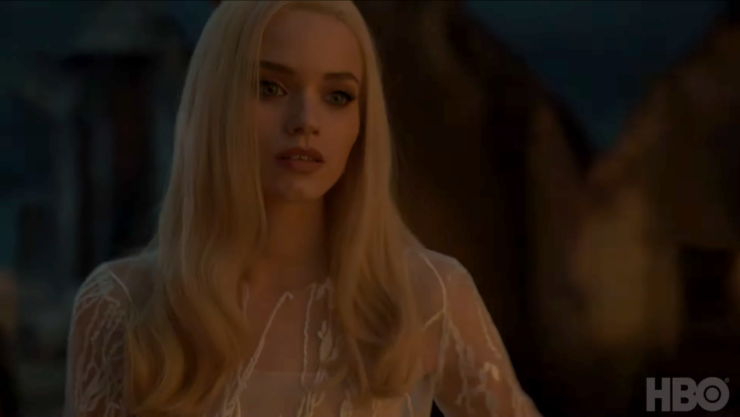

Those choices, by and large, open up possibilities for more nuanced storytelling. By rewriting Caleb Braithwaite—a menacing but fairly standard capitulator to and beneficiary of white supremacy—as Christina and, in casting, the haunted, frail-looking Abbey Lee (who most Americans likely know from her role as one of Immortan Joe’s brides in 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road) in the role, the fight between the Freeman and the Braithwaite branches of the family includes an essential debate about intersectionality. Unlike Caleb’s intergenerational anger at his father for selfishly trying to live forever rather than bequeath him control of the Order of Ancient Dawn, Christina’s anger is also fury at the patriarchy. Though it would be ludicrous to grant equivalency to the treatment of Christina and the Freemans, she too is denied her birthright, having been born in an oppressed body. And that is part of my discomfort with the finale. The entirety of the series builds up places for nuance, and the finale is as heavy-handed as can be.

The Limits of Empathy and Solidarity

Let’s start with the obvious. There is a definite “kill your gays” vibe attached to the choice to kill Ruby (off-screen, no less) in the season finale. In the novel, Ruby’s arc doesn’t include anything about being queer (in large part because Caleb is her patron and, therefore, there is no plot about Christina disguising herself as William). Ruff’s final beat for Ruby is that, after Caleb is defeated, she gets to live on as Hillary Hyde, using magical whiteness as a way to improve her life. It’s an ending that raises a lot of questions and leaves a lot unanswered. The Ruby of the novel never reveals the transformative potion to the Freemans or Leti. There’s ambiguity over whether living in a White body is a blessed escape from the horrors of white supremacy or an act of cowardice, as she leaves her family behind to be hounded by other sorcerers.

The show’s version of Ruby (Wunmi Mosaku) is much more complicated and much more interesting. By having Ruby sleep with Christina-as-William, and by having both Ruby and Christina wrestle with whether they have romantic feelings for one another or if it is simply that Ruby likes having sex with William while Christina likes having sex with women while being in the body of a man, there are thoughtful meditations on the intersection of race, gender, and sexual orientation as well serious and painful beats on whether or not cross-colorist solidarity between women is even possible in an era of racial oppression.

This culminates in episode 8 where Christina, having told Ruby that she doesn’t care about the death of Emmett Till, makes arrangements to endure the same horrifying death (though, she is guaranteed to survive because of her sorcery). It’s a scene that suggests either Christina’s desire to be more empathetic towards Ruby, or her incredible empathic limitations where the only way she can connect to anyone else’s suffering is by enduring it personally. In retrospect, I’m honestly not sure what Green (who both co-wrote and directed the episode) meant to do with that scene… It feels like the first beat in a plot arc that never progresses further. Christina is an embodiment of the white-feminist-as-bad-ally trope and this moment could have either marked the start of some movement away from that.

In the final episode, Ruby and Christina sleep together in their undisguised bodies and admit to one another that neither has slept with a female-bodied person before. And that’s Ruby’s final scene. From there on out, Ruby is dead (or at least brain-dead and kept on life support), and any time we see her, it’s Christina wearing her skin. It feels like a narrative dead-end for both characters. Ruby, who is one of the most nuanced and conflicted characters on the show, is killed off-screen without any resolution to her arc, the better to fool the audience for some unexpected twists later in the episode. Christina, whom the show had been building out as more than a one-note white supremacist villain, becomes one after all, having killed the woman she (maybe?) loves and without ever addressing her attempt to empathize with Ruby by having herself murdered.

Plot-wise, there are gaps I could fill in. I wouldn’t have minded an ending where Christina, faced with the choice between family connection and immortality, chooses the latter and has to be killed as a result. I wouldn’t have minded an ending that explores Ruby’s death and asks questions about what it means to love a White woman as a Black woman in the 1950s and how much one can really trust a person who does not understand their privilege. But none of that makes it on screen, and I find it profoundly disappointing.

A Darker Ending for a Darker Time

And this is where I start to grapple with my feelings about the finale and whether or not those feelings are actual flaws in the show or signs that something is lacking in my approach to criticism of it… I should be clear: I’m an extremely White-passing Latinx person. My name is very Anglo, and I have never been identified as Chicano by anyone going off of outward appearances. Being treated like I am White while being raised in America has absolutely given me profound privilege and made it much harder for me to recognize subtle forms of oppression without stopping to think about it. Perhaps I am too limited in my viewpoint or my knowledge to get a clear answer here to the questions I’m wresting with, but here goes:

Matt Ruff’s novel ends with the Freemans letting Caleb go after cutting him off from all magic. His punishment is to continue to live, understanding what he’s lost. Misha Green’s show ends with all White people being sealed off from magic, Christina included. And, while the Freemans leave her behind, Dee (Jada Harris) returns to kill Christina with her robot arm and her pet shoggoth. Ruff’s novel also ends with a return to the status quo. The Freemans have gotten a little bit ahead in life and stopped a malevolent sorcerer and a white supremacist lodge from trying to kill them. Green’s show, on the other hand, promises a better future at large but is filled with loss in the immediate: Ruby, George, and Atticus are all dead, Dee becomes a killer, Leti and Montrose have to raise Tic’s son without him, Ji-Ah saves the day only by fulfilling her monstrous destiny and killing the man she loves.

Initially, I preferred Ruff’s ending. It’s not just that his ending is less painful with regard to the characters one has come to love, it’s that it leaves the world as it is, mired in the same problems as before. And of course, that’s awful. The Freemans are going to be hunted by other Lodges, there will still be a need for George and Hippolyta’s Safe Negro Travel Guide. There is a part of me that says “that is realism.” My favorite speculative fiction novels use generic conventions to address, contextualize, and express despair at the horrors of the real world instead of offering fictional solutions.

But I suspect that there is a great deal of privilege in that view and that preference. It is easier for me to reflect on a world of horrific injustice because I don’t have to experience it directly. Because of that, I don’t have deep need for a cathartic, fantasy ending where the scales are tipped by the removal of magic from the arsenal of white supremacists. Maybe that apotheosis is more important.

There is also a great deal of privilege in my disappointment with the end of Christina’s arc. Whatever possibilities were realized or unrealized in Green’s gender-swap, there was no way to keep her alive at the end. A voice in my head—one that has been raised to see civility and politeness as tools for reconciliation and not the tools of oppression and silence that they often are—asks, “isn’t it punishment enough that Christina suffers Caleb’s fate—that she lives knowing that she lost and that it cost her everything she thought made her special and powerful?” But that idea, that there is balance in Christina Braithwaite being chastised and brought low, requires one to ignore what Lovecraft Country has already dramatized: the death of Emmett Till, the Tulsa massacre, 500 years of slavery and Jim Crow and white supremacy. There’s a cowardice in that idea.

Maybe, from that perspective, Ruby’s death is not a “kill your gays” failure of the plot (or, at least, not only that), but, rather, a tragic and prudent reminder of the danger of trusting White people—even those who see your humanity. It is telling that the one short story cut from Ruff’s novel is the “The Narrow House,” which contains the novel’s single sympathetic depiction of a White character. In cutting Henry Winthrop and his African American wife, the series makes it clear that exception-that-proves-the-rule White people are a distraction from the inescapable toxicity and horror of American racism.

And there is also a question of both time and audience. Ruff’s novel was published in February 2016, at the very end of the Obama era when, on the surface, further progress seemed inevitable, and it felt obvious that America was (too slowly but still inexorably) moving towards a place of greater racial justice. Green’s adaptation was released in August of 2020, after four years of regressive policies, unchecked police violence, and countless, harrowing disappointments about the future of America. One could get away with characters of color taking the moral high ground against racist antagonists in 2016. It could be read as compassionate. Now, it often reads as naïve at best, sympathetic to white supremacy at worst.

And, for all that Matt Ruff ought to be credited with writing a novel about the African American experience that doesn’t read as pandering or presumptuous (it really is an excellent book), at the end of the day, one has to remember that he is a White man writing for a largely White audience. The perspective he offered in Lovecraft Country was important, but the novel works much better as an excoriation of H.P. Lovecraft than as a meditation on anti-Black racism. It does a brilliant job of proving that one can like problematic things, giving readers a collection of excellent cosmic horror stories in the Lovecraftian vein, while never compromising in its mission to remind you that H.P. Lovecraft himself was a hate-fueled bigot who should not be celebrated.

Misha Green’s series is after something bigger. It is there to welcome Black readers of speculative fiction into the conversation and make White fans rightly uncomfortable about the bones, blood, and trauma underneath the floorboards of their enjoyment. That’s precisely what the end of Lovecraft Country’s first season accomplishes. And, while I may find that ending unsettling—while I may feel disappointed, underwhelmed or, perhaps, justly called out by it—I certainly cannot say that it is ineffective.

Tyler Dean is a professor of Victorian Gothic Literature. He holds a doctorate from the University of California Irvine and teaches at a handful of Southern California colleges. He is one half of the Lincoln & Welles podcast available on Apple Podcasts or through your favorite podcatcher. More of his writing can be found at his website and his fantastical bestiary can be found on Facebook at @presumptivebestiary.